Patenting of Pharmaceutical Drugs in India

A patent is a contract between the society as a whole and the inventor which grants protection to innovators in exchange for disclosure of the invention. It gives exclusive rights to the patent holder and excludes the others from making, using, and selling patented inventions. In this way, a patent gives the inventors the right to exploit his invention and this, in turn, lays down the path to a monopoly in the market for the inventor. This monopoly gives the inventor the necessary motivation to innovate and keep him engaged in continuous quest for finding better or alternative solution.

A patent is a contract between the society as a whole and the inventor which grants protection to innovators in exchange for disclosure of the invention. It gives exclusive rights to the patent holder and excludes the others from making, using, and selling the patented invention. this way patent gives the inventors the right to exploit his invention and this, in turn, lays down the path to a monopoly in the market for the inventor. This monopoly gives the inventor the necessary motivation to innovate and keep him engaged in the continuous for finding better or alternative solutions. However, the law not only has a duty to protect the interest of the inventor, but it has a duty to protect the societal interest also. Thus, drug patenting in the field of pharmaceutical industries is one such prominent occasion where the law has to enforce a striking balance between these two interests.

Pre-TRIPS Era

Act VI of 1856 was the first legislation in India relating to patents. The legislation was based on the British Patent Law of 1852. It used to grant certain exclusive privileges to inventors of new manufacturers for a period of 14 years. Later, replacing all previous legislation and enactments, the Indian Patents and Designs Act, 1911 was introduced which was again replaced by the present legislation the Patents Act, 1970 as far as the patent laws are concerned. The 1970 Patent law was enacted based on the recommendations given by the Ayyangar Committee (1957) which incorporated the proposal that — inventions in the field of medicines and food was to be protected as process patents (process patent does not give the inventor any right on the final product but only on the method of manufacturing) and not as product patents like in other countries. Further, Tek Chand Committee (1949) report suggested principles of compulsory licensing which was incorporated in the 1970 legislation as well. The reason behind adopting process patents over product patents was to avoid the monopoly of a few people in the medicinal field and to ensure access to medicines for all at affordable prices. Another purpose was to help the Indian pharmaceutical companies to grow by producing generic versions of those process-patented drugs.

But soon, this practice was opposed by the developed nations, and the TRIPS agreement was brought on the table in the Uruguay round of GATT (organized by WTO) where Intellectual Properties were introduced as a trade subject. TRIPS agreement mandated that the signatories should implement the obligations of the agreements failing which they will be subjected to international complications.

Post-TRIPS Era

India was a signatory to the TRIPS agreement and as a legal obligation, India had amended its legislation three times to comply with the TRIPS agreement— in 1999, in 2002, and in 2005. Two most significant changes were introduced in the 1970 Patents Act—

-

The first one was the introduction of the present section 3(d) in the Act.

-

The second one was the revocation of the provisions of License of Rights

firstly, the introduction of the present section 3(d) of the Patents Act, 1970 allowed product-patenting of the pharmaceutical drugs. Before, this amendment, product-patents of the drugs were not allowed in India. This came as a major blow to the Indian generic pharmaceutical drug manufacturers. This meant that for generic pharmaceutical drugs manufacturers, not only the process of manufacturing the drugs was prohibited, but the final product (pharmaceutical drugs) became prohibited for them to manufacture or sell also. This led to huge losses to the Indian pharmaceutical industries as the industry then was still not equipped with the proper infrastructure to develop indigenous pharmaceutical drugs.

firstly, the introduction of the present section 3(d) of the Patents Act, 1970 allowed product-patenting of the pharmaceutical drugs. Before, this amendment, product-patents of the drugs were not allowed in India. This came as a major blow to the Indian generic pharmaceutical drug manufacturers. This meant that for generic pharmaceutical drugs manufacturers, not only the process of manufacturing the drugs was prohibited, but the final product (pharmaceutical drugs) became prohibited for them to manufacture or sell also. This led to huge losses to the Indian pharmaceutical industries as the industry then was still not equipped with the proper infrastructure to develop indigenous pharmaceutical drugs.

Secondly, before2002 amendment to the 1970 Patents Act, the Act used to contain a provision for ‘License of right’ which allowed central govt. to endorse a pharmaceutical patent with the words ‘license of right’ so that anyone, who is interested in public welfare, can seek a license to fulfill the requirements of the public. But post the amendment, this provision was repealed and only in a certain situation, in accordance with TRIPS, the central govt. may direct compulsory licensing after giving the patentee a reasonable opportunity to be heard. Further, the central govt. should decide on granting such licenses only on the merit of each case. These restrictions on the national governments of developing countries like India had resulted in the loss of domestic generic pharmaceutical drug manufacturers.

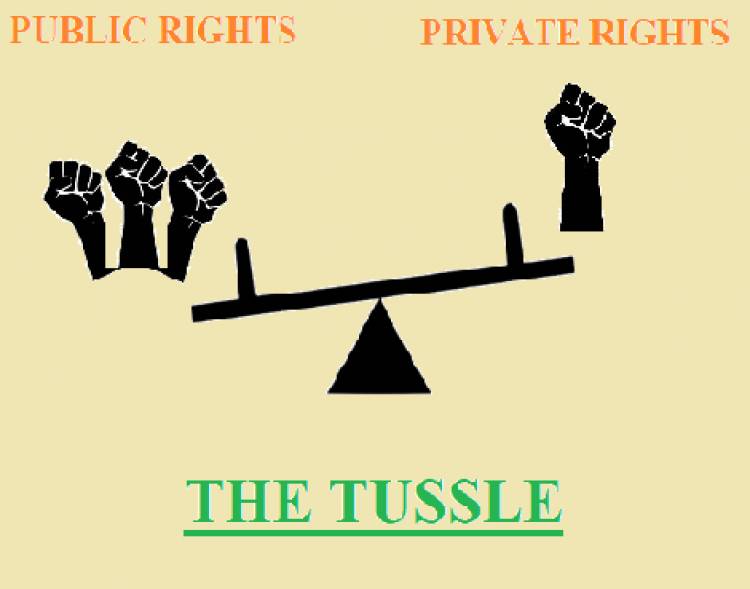

The tussle between Private Rights and Public Rights

The developed countries and the pharmaceutical industry globally are always in favour of monopoly over pharmaceutical drug patents. However, the developing nations, being poor in terms of per capita income, always cared for larger public interest rather than private interest. Also, after independence, India became a welfare state in order to revamp its economy with an aim to get its citizens out of poverty.

Therefore, granting a monopoly over pharmaceutical products and making them less accessible to the poor citizens of this country was not an option. But, commitments to the TRIPS agreement also cannot be overlooked as it would have drawn serious repercussions on the global level. Therefore, the incorporation of the present section 3(d) was provided with certain safeguards so that pharmaceutical companies cannot claim a monopoly over slight modifications to the existing product. There are two ways these safeguards are provided—

-

No monopoly over new form or new property of a known composition/substance

-

No monopoly in the absence of enhancement of known efficacy

These two conditions are cumulative and thus in order to seek patent protection for a pharmaceutical drug, a new form with enhanced efficacy of a drug needs to be established.

In light of this, the first landmark decision came from the hon’ble Supreme Court of India in the case of Novartis Ag v. Union of India, which was the first product-patent case in relation to drugs. Novartis filed a patent application for a drug that was a salt form of the known chemical compound (used for treating cancer). The application was rejected by the patent office on the ground of section 3(d) of the Patents Act, 1970. When the matter reached the Hon'ble Supreme Court, the appellant tried to prove enhanced efficacy by showing that the salt form of the chemical compound has 30% better bioavailability than other forms of that same chemical compound. The court rejected this claim and held that in the case of pharmaceutical products, enhanced efficacy does not only mean physical efficacy; rather it also means “therapeutic efficacy” i.e. whether it cures the disease better than what is already achieved by the existing products. As the salt form of the chemical compound does not show any such enhanced “therapeutic efficacy”, the appellant was denied patent protection. Therefore, if a pharmaceutical drug is granted a product patent for a particular form of a chemical compound, other forms of that drug cannot be granted patent protection unless enhanced therapeutic efficacy is shown. This way, Indian generic pharmaceutical drug manufacturing companies were allowed to manufacture and sell other forms of the patented chemical compound so that the monopoly over the essential pharmaceutical drugs can be avoided.

Conclusion

Public policy is not considered a good argument in the case of pharmaceutical industries. For continuous innovation and for generating better healthcare facilities, proper and adequate incentives should always be made available to the inventors. Otherwise, the innovators will lose interest and the progression of the industry will come to a standstill. However, an regulated monopoly may negate the primary purpose of granting such patents which are to make the invention available to the public. Therefore, establish a balance between these two should be the goal of the patent law. Though, it must be noted that the majority of pharmaceutical market players now in India are Indian companies themselves. Hence, it can be hoped that objections from the international community regarding these disputed provisions can be addressed in near future.

know more about, patents law see the video below-

BY -

DEBKRIPA BURMAN